From Chief Justice to the patent examiner.

Hello, my name is Erik. I’m a lawyer. And I like to do drawings. Would you like to see some of my drawings? Here are some of my other drawings:

On 10/19/05, the daughter of one of my MIT friends shadowed me for a day at work as part of a school project. One of the good things about spending time with children is that it forces you to explain things in simple terms. When my friend’s daughter saw all of the books in my office (yes, we still use books occasionally), she asked, “What’s in all of those books?”

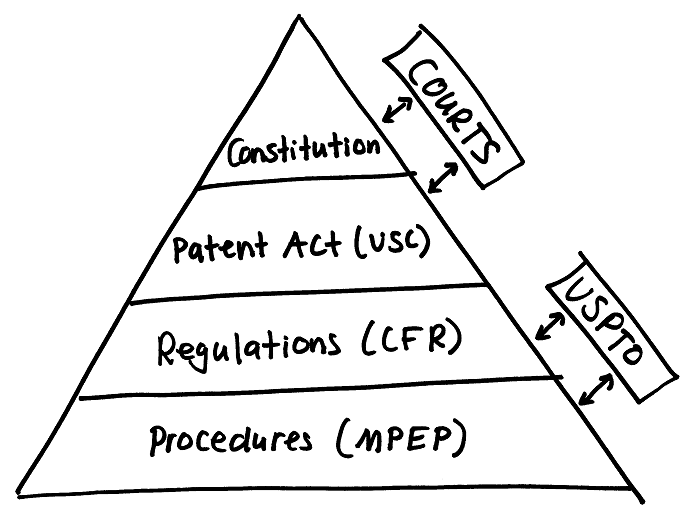

So I drew the above drawing to explain all of the patent laws, how they are related, and how they change.

I drew this as a pyramid with the shorter laws at the top and the longer ones at the bottom.

At the top of the pyramid is the United States Constitution. The structure of our government comes from the Constitution. So do many individual rights. It is our country’s most important legal document. Article 1 Section 8 of the Constitution says:

“The Congress shall have Power … To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries;”

So patent rights and copyright rights come from the same clause in the Constitution. Oddly, the Constitution says nothing about trademark rights. And in our government, the Patent Office and the Trademark Office are combined (in the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO)), but the Copyright Office is separate. So Congress doesn’t always do things the way the drafters of the Constitution thought that they would.

Next in the pyramid (working top to bottom) is the Patent Act. When our lawmakers in Congress (the Senate and the House of Representatives) want to make a new law, they write it, debate on it, and if they agree on it, then the new law becomes part of the United States Code. The United States Code is divided into smaller pieces called titles, parts, chapters, and sections. The Patent Act is the short name for our patent laws, which exist in Title 35 of the United States Code (35 USC for short).

The version of the Patent Act that I use is about 88 pages long. So the Constitution says one sentence about how Congress can create patent laws, and Congress created 88 pages of patent laws.

Next in the pyramid is the Patent Rules (also called patent regulations). Congress writes the laws, but different agencies of the government have to carry out those laws. The Federal Rules are the rules that the agencies write to help explain the laws and how they’ll be carried out. For patent laws, the USPTO writes the Patent Rules, and those appear in Title 37 of the Code of Federal Regulations (37 CFR for short).

The version of the Patent Rules that I use is about 336 pages long. So we’ve gone from one sentence (Constitution) to 88 pages (Patent Act) to 336 pages (Patent Rules).

The bottom of the pyramid is the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP). The MPEP was written by the USPTO for patent examiners to help them do their jobs. Most patent examiners are not lawyers. So the MPEP is designed to help them understand and apply patent law (the Constitution, the Patent Act, and the Patent Rules). The MPEP is the most frequently used reference book for patent examiners. So it is helpful for patent lawyers like me to know the MPEP.

The version of the MPEP that I use is about 3000 pages long. So we’ve gone from one sentence (Constitution) to 88 pages (Patent Act) to 336 pages (Patent Rules) to 3000 pages (MPEP).

The fun part about the patent laws is that they are constantly changing. The job of the courts (and ultimately the Supreme Court) is to determine what the law is – what it means. So whenever there is a patent dispute that ends up in court, the courts will be interpreting what the patent laws (the Constitution and the Patent Act) mean. Congress can also change the Patent Act, but that is harder to do. And the people of the United States can change the Constitution, but that is even harder to do.

At the same time, the USPTO is constantly revising the Patent Rules and the MPEP. And sometimes the way the USPTO thinks the patent laws should be applied differs from how the courts think the patent laws should be applied.

Summary

My drawing could be better. And my explanation could be better. But again, I drew this for a child, so it’s a good place to start. The main point is that there are four types of patent laws: the Constitution, the Patent Act, the Patent Rules, and the MPEP. And patent practitioners like me have to do lots of reading to keep up with all of the changes. Ultimately, the Constitution’s patent clause is the most important patent law. But on a daily basis, the MPEP is the most important document for a patent lawyer.

[EDITOR’S NOTE: In the summer of 2025, Clocktower Intern Mark Magyar used artificial intelligence (AI) software to shorten over 100 Clocktower articles by 17%. The shortened articles are included as comments to the original ones. And 17 is the most random number (https://www.giantpeople.com/4497.html) (https://www.clocktowerlaw.com/5919.html).]

* Drawing That Explains Patent Laws

From Chief Justice to the patent examiner.

Hello, my name is Erik. I’m a lawyer. And I like to do drawings. Would you like to see some of my drawings? Here are a few others:

Drawing That Explains Copyright Law

How To Debug Computer Problems

On 10/19/05, the daughter of a friend shadowed me for a school project. Kids are great because they make you explain things simply. When she saw all the books in my office, she asked, “What’s in all of those books?”

So I drew this to show how patent laws fit together and how they change.

I sketched a pyramid with short laws at the top, longer ones at the bottom.

At the top sits the U.S. Constitution, our most important legal document. Article 1 Section 8 says:

“The Congress shall have Power … To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries;”

Patent and copyright rights come from this clause. Oddly, the Constitution says nothing about trademarks. Yet today, patents and trademarks share the same office (USPTO), while copyrights have their own office.

Next in the pyramid is the Patent Act, found in Title 35 of the United States Code. When Congress makes new laws, they become part of the Code. The Patent Act runs about 88 pages—quite a jump from one sentence in the Constitution.

Below that are the Patent Rules, written by the USPTO to explain how to apply the Patent Act. They’re in Title 37 of the Code of Federal Regulations and total about 336 pages.

At the base of the pyramid is the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP). This 3,000-page guide helps patent examiners—most of whom aren’t lawyers—understand and apply patent law. It’s the most-used reference in the field, so patent lawyers know it well.

So we’ve gone from one sentence (Constitution) → 88 pages (Patent Act) → 336 pages (Patent Rules) → 3,000 pages (MPEP).

Patent law is always shifting. Courts, including the Supreme Court, interpret what the Constitution and Patent Act mean. Congress can amend the Patent Act (hard), and the Constitution itself (harder). Meanwhile, the USPTO regularly revises the Patent Rules and the MPEP—sometimes in ways courts disagree with.

Summary

My drawing and explanation could be better, but for a child it worked. The point: there are four layers of patent law—the Constitution, the Patent Act, the Patent Rules, and the MPEP. Practitioners must read constantly to keep up. The Constitution provides the foundation, but day to day, the MPEP is what patent lawyers use most.