And what’s wrong with law school education.

Hello, my name is Erik. I’m a lawyer. And I like to do drawings. Would you like to see some of my drawings? Here are some of my other drawings:

- Drawing That Explains Patent Laws

- Drawing That Explains Copyright Law

- How To Debug Computer Problems

On 10/19/05, the daughter of one of my MIT friends shadowed me for a day at work as part of a school project. One of the good things about spending time with children is that it forces you to explain things in simple terms.

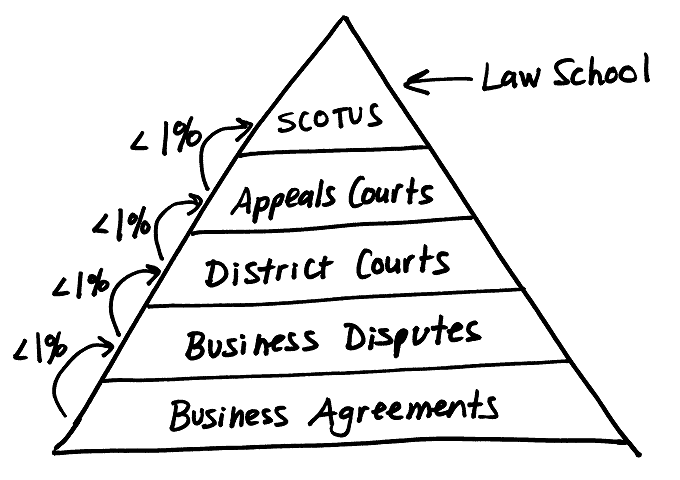

When my friends daughter asked about litigation, I drew the above drawing.

There are millions of business agreements that proceed without dispute. A small percentage of business agreements (let’s say fewer than 1%) end up as business disputes. A small percentage of business disputes result in law suits being filed in district courts. A small percentage of district court rulings are appealed to appeals courts. And a small percentage of appellate cases make it to the Supreme Court of the U.S. (or “SCOTUS” for short).

Unfortunately, what law students (at least in the U.S.) study is mostly Supreme Court (and appellate court) decisions. It’s important to understand the law and how it evolves, and reading appellate cases definitely helps. But learning how to practice law by reading case law is like learning how to drive by reading your car’s owner’s manual. If you try to modify your practice of patent law by reading appellate case law, then you end up doing what I like to call “drafting to the exception,” a practice that tries to avoid making mistakes by focusing on the mistakes of others in the exceptional case that makes it through the appellate process.

As parents, we learn that children move towards the pictures that we create for them. If we say “Don’t spill the milk,” then all they are thinking of is “spilling the milk.” Instead, we should say “Hold the cup with two hands,” or whatever advice is appropriate.

There is a scene from American Beauty, where the mom, Carolyn Burnham, says after her daughter’s cheerleading performance, “Honey, I’m so proud of you. I watched you very closely, and you didn’t screw up once!”

Focusing on not screwing up once is drafting to the exception.

Draft to the rule, don’t draft to the exception.

Patents need to operate in the real world – the real business world. Those who focus on how they operate in court are missing the point. If all that patent practitioners produce are incomprehensible pieces of paper that will stand up in court, then they have done their clients no favors. Patents only have value when the things they protect can be made, used, and sold effectively, and a good patent can make this happen.

If patent practitioners draft patents that easy to understand, then they will have happy clients. Clients who are able to license, litigate, sell, and defend their patents successfully. Clients whose patents will not likely end up in court. And if they do, then they won’t suffer the same fate as those we read about in textbooks and law journals.

So at Clock Tower Law Group, we believe that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, and the best prevention is writing clearly and concisely.

Summary

My drawing could be better. And my explanation could be better. But again, I drew this for a child, so it’s a good place to start. I drew this as a pyramid because I often think of the law as an iceberg. Appellate court decisions are the tip of the iceberg. But you need to understand what’s lurking beneath the surface to successfully navigate your clients through treacherous waters.

[EDITOR’S NOTE: In the summer of 2025, Clocktower Intern Mark Magyar used artificial intelligence (AI) software to shorten over 100 Clocktower articles by 17%. The shortened articles are included as comments to the original ones. And 17 is the most random number (https://www.giantpeople.com/4497.html) (https://www.clocktowerlaw.com/5919.html).]

* Drawing That Explains Patent Disputes

And What’s Wrong with Law School Education

Hello, my name is Erik. I’m a lawyer. And I like to do drawings. Would you like to see some of my drawings?

Drawing That Explains Patent Laws

Drawing That Explains Copyright Law

How To Debug Computer Problems

On 10/19/05, the daughter of one of my MIT friends shadowed me for a school project. Time with kids forces you to explain things simply.

When she asked about litigation, I drew the above.

There are millions of agreements that proceed without dispute. Fewer than 1% turn into disputes. A fraction of those lead to lawsuits. Fewer still reach appellate courts. And an even smaller fraction make it to the U.S. Supreme Court (“SCOTUS”).

Yet law students mostly study Supreme Court and appellate decisions. Understanding how law evolves is useful, but trying to learn practice this way is like learning to drive from your car’s manual. It leads to what I call “drafting to the exception”—avoiding mistakes by focusing only on rare appellate cases.

As parents, we know kids move toward the pictures we paint for them. Say “Don’t spill the milk,” and they think only of spilling. Better to say “Hold the cup with two hands.”

In American Beauty, Carolyn Burnham tells her daughter after a performance: “I watched you very closely, and you didn’t screw up once!” That’s drafting to the exception.

Draft to the rule, not the exception.

Patents must work in the business world. Drafting only to withstand court scrutiny misses the point. A patent has value only if what it protects can be made, used, and sold. Clear, usable patents serve clients best—they help them license, litigate, sell, and defend their IP, and often keep them out of court entirely.

At Clock Tower Law Group, we believe an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. And the best prevention is writing clearly and concisely.

Summary

My drawing could be better, my explanation too. But I drew it for a child, which makes it a good starting point. I used a pyramid because I see law as an iceberg: appellate decisions are the tip, but you must understand what lurks beneath to guide clients safely through treacherous waters.